“The walls and grids that restrain your animals restrain also your own knowledge.”

“The walls and grids that restrain your animals restrain also your own knowledge.”

— Vicki Hearne

What I call “old-school” dog trainers — those who operate from the assumption that the human has “to be the alpha” in his or her relationship with a dog — don’t, in my opinion, credit dogs with much in the way of cognitive ability.

Some, like the 1920-era European trainer Konrad Most, bluntly state an approach to education that many of us would recoil from today: “In the absence of compulsion, neither human education nor canine training is possible.” Others, like William Koehler (circa 1960s), give rational-sounding advice: “Lay down a set of rules, and see that your dog lives by them.” But the means used to accomplish that goal are harsh and authoritarian.

What these trainers share is an emphasis on punishment over motivation or reward and an expectation that a dog should offer instant, precise obedience to any command given by a human. The expected response is almost robotic in its uniformity and immediacy.

Trainers with these expectations do not believe that dogs can — or should — think or be part of a decision-making process. No, the dog should know who’s boss and, according to Most, “do what we find convenient or useful and refrain from doing what is inconvenient or harmful to us.”

While both Most and Koehler were both enormously influential in the development of dog training, much about their approach is antithetical to the goal of raising a thinking dog.

Demanding instant, precise obedience to all commands in all situations does not allow for the dog to think or process the command in any way. When you expect instant, unquestioning obedience from your dog, you are essentially prohibiting him from thinking. In human relationships, we talk about such expectations this way: “When I say jump; you may ask only, ‘how high?’ ”

To raise a thinking dog, that is, to use a cognitive approach to your dog’s education, you must have expectations that not only allow for but encourage the dog to think and solve problems. The cognitive dog needs to learn, understand, and, ultimately, buy into a shared goal. Expecting unquestioning obedience at every request, mapping out not only the end result but every step the dog must perform to get there does not — cannot — allow dogs to think conceptually about what you are trying to accomplish, learn to solve problems, or offer a different (maybe better!) solution.

Granted, there are situations where an instant response is necessary — if your dog is unthinkingly following a bouncing tennis ball into a street, for example. But developing your dog’s cognitive abilities does not prevent you from also teaching your dog a strong recall and an “emergency recall” cue that, when taught and practiced with the highest-value treats possible, will ensure an automatic response in a true emergency.

There are many ways to lead or manage (or parent). Those of us who want to share our lives with thinking dogs should be wary of dog professionals who talk a lot about alpha roles and hierarchical relationships. Instead, we should look for ways to develop our dogs’ considerable cognitive abilities. Start by figuring out what motivates your dog. Read future blogs for tips on how to do that and more.

dogs

Are dryer sheets dangerous to dogs?

Cali loves to grab the dryer sheets that often fall to the floor when I am folding clean laundry. It never occurred to me that her habit of grabbing and shredding them could be a problem … until I read this blog post: Four Household Dangers. Keep your puppies safe!

Teaching or Training?

Puppies, like babies, are born with the potential to learn and problem solve and think. They are innately curious and begin investigating their world even before they open their eyes.

Our job is to develop these skills in our puppies and dogs by providing opportunities for them to learn and develop their conceptual thinking abilities. We can expose them to lots of novel items and situations and provide encouragement and motivation. We can also be on the lookout — especially with puppies — for opportunities to turn potential problem behaviors into desirable, adorable, and even helpful skills!

Dogs who are taught, especially by handlers who use methods that encourage problem-solving, become better problem-solvers. A study called “Does training make you smarter?” compared dogs who had received training with dogs who had not. Dogs who had received training solved a problem — opening a box that had a pad that could be pressed by the dog’s paw — spent more time trying to open the box (and were less likely to seek help from their owners) than dogs who had no formal education. The study’s authors speculate that trained dogs have “learned to learn” in a way that unschooled dogs have not.

But, and this is a big but — not all education is equal. There are many approaches to teaching or training, and the methods you choose will affect more than just how fast your dog learns — it can affect the bond between you and your dog, and it can shape or reflect your attitudes toward dogs. And it’s not just the method. The words matter, too.

I make a distinction between training dogs and teaching them because I think the word choice reflects a difference in attitude and goals.

Training dogs is what I call educational approaches that are narrowly focused on eliciting specific reactions to cues or commands. The trainer has a clear end result in mind for each command. The trainer says, “sit;” the dog sits. Practice emphasizes precision of the dog’s response, speed of the response, and the dog’s ability to respond quickly and precisely even when distractions are present.

When I refer to teaching, on the other hand, I am referring to a process that develops the dog’s thinking and problem-solving abilities. The teacher’s goal is to give his or her students the tools and the confidence to figure out what to do in a variety of situations. Sometimes, a teacher might seek a precise response, like the sit; other times, the teacher makes a request that requires the dog to figure out what to do. “Find a pen” gives the dog a goal but no precise instructions for reaching that goal.

Teaching brings the dog to a level of independent thought and problem solving that enables him to respond to a command or cue that is as vaguely defined as “find a pen;” training does not.

Any approach to training or teaching is based on an underlying mindset or set of assumptions: assumptions about what dogs are capable of learning; assumptions about how dogs learn and how much of what we say and do they actually understand; and assumptions about what the dog-person relationship should be.

Trainers who do not believe that dogs are capable or reasoning or problem-solving are unlikely to put any effort into developing these skills in the dogs they train. Trainers or handlers who believe the dog’s “job” is to be obedient and submissive are unlikely to tolerate a free-thinking dog. Some trainers talk about “getting dominance” or “being the alpha” as ways to ensure that dogs remain obedient and submissive.

Methods of dog “training” or education can be placed on a continuum that ranges from those that do not encourage the dog to think at all to those that practically make the dog do all of the thinking. The Thinking Dog blog will teach you to recognize various approaches and their goals — and encourage and equip you to explore methods that help your dog become the best thinking dog he or she can be.

The Great Outdoors

We’re about to embark on our first camping adventure. It will be camping-lite, with lots of people and dogs heading to a group campsite at a family “camping resort.” Nothing too ambitious for us city girls.

I’ve been fortunate to be able to borrow needed equipment from friends who will also be on this adventure. But what about Jana and Cali?

What great luck, then, that I got an email from doggyloot (visit at your own peril; the site can be dangerous) titled “Make your pooch one happy camper!”

With great relief, I opened the email to see what gear my girls would need for their weekend in the woods.

How about a dog bed that converts to a sleeping bag? Add to that a comfy dog-size tent. The tent has windows on three sides (with nylon covers to block the light) and a zip-close door, also with mesh screen and solid flaps. Does each dog need her own, I wondered. Can they share? Why can’t we all bunk together? A less-fancy option is a shade shelter, which is essentially a tent with one fully open side — no door, mesh or otherwise.

How about a dog bed that converts to a sleeping bag? Add to that a comfy dog-size tent. The tent has windows on three sides (with nylon covers to block the light) and a zip-close door, also with mesh screen and solid flaps. Does each dog need her own, I wondered. Can they share? Why can’t we all bunk together? A less-fancy option is a shade shelter, which is essentially a tent with one fully open side — no door, mesh or otherwise.

For hiking, an insect-repellent bandanna is recommended, a travel first-aid kit, and perhaps a doggy backpack to carry the gear. And, since tenderfoot pooches work up an appetite on the trail, some Turbopup doggy meal-replacement bars, available in bacon or peanut butter flavor. Yum. Add some doggy wipes for on-the-trail grooming needs and an insect-repellent blanket for use in camp, and they will be all set …

And I was just planning to pack some beef-bison jerky (they are addicted), a couple of chew toys, and their swim suits. Silly me. Maybe I should revisit my original idea — a doggy camper, like these, featured on HuffPost not long ago. After all, my princesses are not used to roughing it.

What Is Cognitive Education for Dogs?

Welcome to an all-new, improved Thinking Dog blog! It is re-launching with a new focus — cognitive approaches to educating dogs.

What does that mean? Think of it as a contrast to the more traditional approaches, many of which use force, to train dogs.

Cognitive-based dog education means teaching dogs to think their way to becoming their best selves.

Their best what, you ask? Well, that answer is different for every dog — just as it is for every person.

It’s not a new idea: In 1963, Clarence Pfaffenberger wrote a book called The New Knowledge of Dog Behavior. A line in that book beautifully captures the essence of cognitive education. Pfaffenberger writes that the first time a puppy to removed from his or her littermates for training, the puppy is given “the dignity of being an individual.” All dogs deserve this. It is this understanding that forms the basis of cognitive education for dogs.

In 1995, Vicki Hearne published a classic piece, “A Taxonomy of Knowing: Animals Captive, Free-Ranging, and at Liberty.” In it, she describes the ideal relationship between a human and a non-human partner (most of her examples are dogs): the team shares a goal, recognizing and respecting the unique abilities that each member of the team brings to the joint pursuit of that goal.

An animal working at liberty, Hearne writes, is one “whose condition frees her to make the fullest use of some or all of her powers.” A great example is a search-and-rescue team. The dog brings amazing powers of scent detection and tracking to the partnership; the human brings logistical planning abilities and much more. The point is, neither partner, alone, could be as successful in the goal of finding a lost child as they are as a team.

Dogs in at-liberty partnerships are being the best that they can be. Cognitive education can get you and your dog there.

Remember Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Psych 101)? Basic stuff like food and shelter are at the bottom. More esoteric needs, like social acceptance and aesthetic enjoyment, are higher up. The highest level is self-actualization — being the best you that you can be. That is what cognitive educators want for each and every dog.

As Pfaffenberger acknowledged, each dog is a unique individual with likes, dislikes, strengths, weaknesses — and an idea of what he or she wants (and does not want) to do. Cognitive educators understand this and teach each dog as an individual. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to training.

This approach enables each dog to be the best (fill in the blank) that he or she can. Some dogs can become fantastic service dogs; others are destined to work as scent detection or search and rescue dogs, serve in the military, or provide loving companionship to their humans. Some pets are great athletes who enjoy dock diving; others prefer Rally, flyball, agility, or freestyle dancing. Whatever your pet’s skills and preferences, you, as a cognitive educator, friend, and companion to that dog, can help your dog explore and develop and grow.

If this sounds like something you believe in or want to learn more about, stick with The Thinking Dog blog. We’ll be exploring cognitive education from every angle — who does it and how; what it looks like in daily life; how to think like a cognitive educator; what dogs are telling you about their likes and dislikes and how to better understand them … and so much more.

Check back often, subscribe to the blog, and be sure to share it with all of your dog-loving friends.

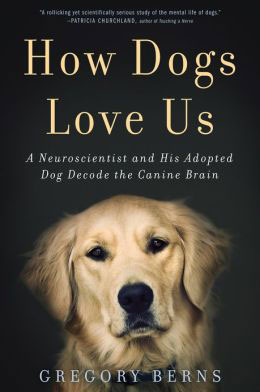

How Dogs Love Us

Gregory Berns got the crazy idea of training his dog to lie still in an MRI machine, in the hope it would provide some insight into dogs’ thinking. What he found brings scientific proof to something every dog person knows — that dogs read us, anticipate our behavior, and act on that knowledge. Dogs, in short, have theory of mind. Berns rightly argues that this scientific evidence must change the way we think of and treat dogs.

Gregory Berns got the crazy idea of training his dog to lie still in an MRI machine, in the hope it would provide some insight into dogs’ thinking. What he found brings scientific proof to something every dog person knows — that dogs read us, anticipate our behavior, and act on that knowledge. Dogs, in short, have theory of mind. Berns rightly argues that this scientific evidence must change the way we think of and treat dogs.

What’s especially wonderful about this story is that, at least at the beginning, Berns is not an especially savvy dog person. He loves his dogs, treats them extremely well, but hasn’t spent a lot of time trying to communicate effectively with them or train them. By the end of the book — or maybe by a few months into the research — he’s become convinced that dogs communicate and function on a very high level and that “the key to improving dog-human relationships is through social cognition, not behaviorism.” Quite a journey … in fact, it’s the same journey that I hope to push my students along in Bergin U classes on dog training, canine-human communication and understanding the dog’s perspective. (Any current Bergin U students reading this might as well order their copies now … this book is destined to become required reading in all my classes.)

The book is filled with fairly complex scientific concepts, but it is written beautifully and clearly. It is very easy to understand and, like a good adventure novel, pulls readers along with foreshadowing and suspense. I especially love the long discussion of the ethical issues Berns and his team faced in setting up the research and the insistence of all the human researchers that the dogs would always be free to opt out, at any time. I also love the dog-centric approach the research takes (read the book to find out what I mean!). This book — this whole research study —is a testament to the amazing possibilities that exist when humans acknowledge their dogs’ abilities, treat them as partners (rather than as property or as slaves), and engage with them in a respectful, positive manner.

Because I am nut for precise language, I do have to quibble with the title. Berns does not actually show HOW dogs love us. He does show, I believe, that they DO love their human family members. While he can’t really show us what dogs are thinking, though, he has shown a way to understand their likes and dislikes — and perhaps opened the door to a better ability to read in dogs other emotions that humans and dogs share.

What are the BEST dog toys?

A friend recently asked me for advice on addressing some behavior issues with a young golden retriever. Since I have extensive experience with young golden retrievers, I quickly deduced that the main issue was that the golden’s energy level far surpassed that of her human. She needed a way to burn off some of that energy, something that would provide mental stimulation as well. Bored, smart dogs with energy to burn can be a dangerous combination!

I suggested several chew toys and treat toys, both of which will engage the attention of food-motivated dogs (goldens define food-motivated) and pose a mental challenge. In other words, burn off physical and mental energy, keep the dog busy, and make everyone’s life a little more peaceful. Sounds great, right?

These toys work for any dog who is willing to put some effort into obtaining a yummy reward. All have been thoroughly vetted by an expert panel consisting of:

- Jana, a 10-year-old golden who will work for hours for the tiniest morsel of food

- Cali, an 11-month-old golden who has about a 20-second attention span, but who enjoys most of these toys and will actually play with some of them for as long as half an hour (!!)

- Albee, a 2-year-old Labrador who prefers not to have to work for her food after spending a long day at the office, but who also enthusiastically approved several of these toys

Chew Toys

Our newest favorites are all in the “Busy Buddy” family — The Bristle Bone, which is used with rawhide or cornstarch rings, is beloved by all three expert testers. Albee has managed to de-bristle the bristle rings, though, which makes it really easy to get the rawhide and also diminishes the teeth cleaning action of the toy. The Jack toy is Cali’s favorite, but Jana has managed to take it apart several times, making it far too easy to slip off the rawhide ring and devour it. The Ultra Stratos is a new addition to this toy collection and seemed promising, but again, Jana managed to defeat it fairly quickly. Now that we have several of these Busy Buddy toys, I make up new configurations of rings, bristles and rawhide, and I am going to get smaller rings to make it even harder for top expert Jana to get to the rings. Still, she will spend a good hour chewing on one of these toys if I manage to screw it together tightly enough. In my book, that is a huge success.

I can’t write about chew toys without mentioning old standbys: Rawhide, bones, Nylabones, and antlers.

All members of the expert panel love antlers, but I stopped getting them because we got a soft one once; Jana managed to eat a couple inches of it before I noticed, and she got really sick. In general, though, they are safe, long-lasting chews. If you get them, purchase from a U.S.-company that uses wild-shed antlers. Antlers don’t splinter like bones, and they are all natural.

Bones can be OK if they are fresh, boiled just a couple min to kill germs. When they’ve been around a while, they get brittle, though, and they can splinter or crack. That is how Jana cracked a molar recently, a very expensive lesson! We sometimes get the ones with some gristle still on, give them to the dogs outside (separated so they don’t kill each other) and throw them out when the bone part starts to look dry.

Cali has recently discovered Nylabones, and she’s a big fan. Jana and Albee will occasionally get into a chewing frenzy as well. These last a long time and are safe chew toys.

I generally avoid rawhide, since dogs can bite off large enough chunks that they can choke, and since most rawhide is treated with really toxic chemicals. There are some U.S. made brands that claim to be organic, but I still stay away from rawhide. There are so many preferable toys to choose from.

Treat Toys

These are great for mental stimulation as well as fun. You can feed the dog part of each meal in one or more of these, which will burn some mental energy.

Our experts give 4 paws up to:

Our experts give 4 paws up to:

- The classic Kong, stuffed with … just about anything. Some favorites are kibble mixed w/peanut butter or yogurt and frozen; kibble softened in chicken broth (or warm water) and frozen; plain yogurt (also frozen) — this one is messy and best enjoyed outside. There are literally hundreds of Kong “recipes” if you Google “Kong stuffing.”

- Squirrel Dude is still the reigning champion at our house. Jana loves him and cannot get all the food out. (The other dogs are less willing to work that hard, but he’s very popular will all testers.)

- Busy Buddy Twist n’ Treat — good with peanut butter and kibble. Plain kibble falls out too easily.

- Kong Genius toys are challenging — Cali hasn’t mastered them yet! Jana loves them. Albee doesn’t want to work that hard. They link together to make it even harder to get the food out.

- Other favorites, beloved by Albee in particular, are the Omega Paw Tricky Treat Ball and the TreatStik. These both hold kibble and the dog bats the toy around to make the kibble fall out.

- And of course, Jana’s longtime favorite, the Orbee ball with a large biscuit stuffed inside. She has to break the biscuit into small enough pieces that they will fall out of the small hole. She’s gotten so good at this, though, that unless the biscuit is very hard to break, she’s done in a few minutes.

General advice — Avoid toys that use a specially designed treat. The refill treats are usually overpriced. There are many, many toys that can be filled with the dog’s kibble, which means you can make the dog work for part of each meal. The only exception I’ve made is the Busy Buddy toys, because they are among the few toys that keep Jana busy for hours (really!) and the rings last a while. I also advise avoiding the ones that are a harder plastic (like the Buster Cube); they are very noisy on the floor as the dog bangs them around to get the food out.

This stuff is all available on Dog.com and Amazon. Local St. Petersburgers can get them at Pet Food Warehouse, a wonderful, locally owned pet store. If you get on their email list, you get a monthly newsletter with a $5 coupon!

Dogs Are Not Merchandise

Cali at 9 weeks: Too small to travel alone

The USDA recently revised its definition of a “pet store” to target breeders, primarily puppy mills, that sell dogs online. In a nutshell, people who sell large numbers of pets must now sell them in a place (retail store, home, public space) where the buyers can see the animals before purchase. (Read the new rules and find out more here and here.) Previously, anyone who sold pets directly to pet owners could identify his or her business as a “retail pet store” and be exempt from licensing and inspection requirements that apply to commercial animal breeders but not to pet stores. This loophole was exploited by large-scale breeders, who called themselves retail pet stores because they sold pets directly to customers online. Thus puppy mills could escape any kind of oversight or regulation. (Large-scale breeders who sell only to pet stores are a whole different category and, unfortunately, are not affected by these regulations.) There is a list of exceptions, notably most shelters and rescue groups, working dog breeders, and people with fewer than five breeding animals.A Facebook group of service dog trainers that I participate in has been discussing these changes. Many participants in this Facebook discussion are furious about the new rules, claiming they are an attack on small breeders. I’ve read the regulations, though, and from my reading, it’s clear that the regulations don’t apply to anyone with fewer than five breeding females or to service dog breeders.

It seems to me that requiring people to meet the buyer / seller of a dog makes sense. I also think that having some oversight of people breeding large numbers of dogs is a good thing — though I do not for a moment believe that government regulation will solve all problems and make puppy mills disappear. I think that consumers have to make that happen simply by not buying from irresponsible breeders or pet stores. The worst fallout that I can see is that some medium-sized breeders might have to get licensed under these new rules, but if they treat their animals well and run a clean, safe operation, they should have nothing to worry about.

If you see something in these rules that I am missing, please post your comments here. The more people who care and who talk about issues of responsible dog breeding and sales, the better. But, right now, the new rules seem like a good start to me.

In the discussion, someone pointed out that the AKC opposes the rule change. I commented that that was not surprising; purebred puppy mill puppies are the AKC’s largest revenue source. One poster called this statement inflammatory and the farthest thing from the truth.

While I cannot pinpoint how many AKC-registered dogs and puppies come from puppy mills, certainly anyone who’s ever been active in dog rescue knows that there are an awful lot of them, compared with relatively small numbers of dogs from quality breeders. And puppy and dog registrations are by far the largest source of AKC revenue, earning the AKC more than $25 million in 2012.

I did not mean my statement to be inflammatory, either. I merely meant to point out that an organization with a huge financial stake in the sale of puppies naturally opposes any restriction of those sales. Therefore, the AKC might not be the best judge of whether the rules are desirable.

Critical thinking is needed when we think about how dogs are bred, bought and sold. While I don’t think that the AKC is evil, I certainly don’t think that it always places dogs’ best interests above its own financial interests. It is a business. A business that makes a lot of money from registering puppies.

The AKC has a long and sordid (and well-documented) history of willingness to register any purebred puppy, regardless of health. (Read some of Donald McCaig’s work if you’re interested in finding out more — for example, “The Dog Wars,” chronicling the opposition of many border collie breeders and breed enthusiasts to having the breed become an AKC breed.)

Some breed clubs, mostly in Europe, will register an animal for breeding only if the dog passes certain health clearances. The AKC does not take this logical step. The AKC is a large, influential organization. It could do a lot to improve the health and welfare of purebred dogs. In many instances, it chooses not to.

While many breeders are ethical people who truly love their dogs, for others, dog breeding is just a business. Hence puppy mills. And unscrupulous breeders who will breed from a champion dog that has known genetic issues — issues that could easily be eradicated simply by not breeding dogs who carry the genes. All of this, apparently, is fine with the AKC, which registers these puppies and collects its fees. This alone is enough to thoroughly discredit the AKC in my mind.

Despite what many dog owners believe, the mere fact that a dog is purebred does not mean that the dog is healthy or well-bred. It does not mean that the dog has a good temperament. It does not mean that the puppy did not start life in horrible, cruel circumstances. All it means is that the dog’s parents were registered (by the AKC, for a fee) as purebred. And their parents were, and so on.

While many things about purebred dog breeding make me somewhat uneasy, I do understand the allure of purebred dogs. I have done a lot of work with service dogs. Being able to (somewhat) predict a dog’s temperament and aptitudes based on the dog’s breed and pedigree is definitely helpful. I do understand the need for some breeding of purebred dogs and for a registry of those dogs.

But I don’t think that requiring breeders to follow minimal rules to ensure that their dogs are bred humanely, kept healthy and treated well is unreasonable. I don’t think that forbidding most sales of dogs via the Internet, between strangers, is unreasonable. And I don’t think that the AKC should get to write or influence the rules.

A dog is not merchandise, like books or a pair of shoes, that can reasonably be bought and sold online and shipped to buyers. Acquiring a dog is acquiring a family member. Ordering an unseen dog from strangers (who could be lying about any and every detail of their operation) is a terrible idea. Sending small puppies on long plane flights in crates, terrified and alone, is a terrible idea. (Pet stores are horrific places to buy or sell puppies too, and, unfortunately, this law does not tackle that issue.) But there are hundreds, maybe thousands of breeders who breed and sell puppies simply to make money. They do not think about the dogs as living, thinking, feeling beings. They do not care whether the buyer will treat the puppy well or whether the plane flight will traumatize the puppy. They think of the puppies — and treat them — as merchandise. Like a pair of shoes or a book. I find that reprehensible.

A responsible breeder would not sell a puppy to a total stranger. A responsible breeder would not pack a puppy into a crate and drive him to the airport and send the crate as cargo for a stranger to pick up at the other end. A responsible breeder makes sure that the adopters are the right people for that puppy and they will take proper care of the puppy — starting with picking up the puppy in person or sending a trustworthy emissary. A responsible breeder will take back any puppy that is not a good match for the adopting family. These breeders are not the target of this law. Even if they have more than four breeding dogs and now need a license, they should have nothing to fear, since a responsible breeder no doubt keeps her dogs in humane, clean conditions.

This new regulations are not ideal. They are not without problems. They certainly don’t solve the problem of puppy mills. But, to me, they seem like a good start. If we dog people want to make life better for dogs, we should save our anger for the many worthy targets. And use our passion and our energy to educate dog owners about where to — and not to — buy puppies.

10 Years Young — Laser Treatments Reduce Jana’s Arthritis Pain

Jana has just finished a course of cold laser therapy. With the zeal of the newly converted, I am here to sing the praises of this treatment for arthritis.

Let’s back up a little. Jana has had arthritic elbows and back and, unknown to me, hips, for a while. In the last several months, she has been noticeably more stiff and sore more often. She’s had regular chiropractic adjustments for years, and these have been very helpful. But it was no longer enough.

Very reluctant to put her on medication for the rest of her life, I started checking into other therapies. A vet in California mentioned cold laser therapy. It sounded promising; it is not invasive, has no side effects, and has helped many dogs with painful injuries or arthritis. But, I was about to drive back to Florida, so I decided to wait until we got back to Florida to start.

Fast forward to now. Our vet here in St. Petersburg does laser therapy in his office, so we scheduled some X-rays to see where Jana needed attention and took the plunge.

The X-rays showed a lot more damage than I expected and explained Jana’s morning stiffness, reluctance to walk or play, and general grumpiness of late. That was about 3 weeks ago. Six laser sessions later, Jana is actively soliciting play, swimming, and catching balls, and she is happier than she has been in months. She’s less stiff and more cuddly. She is clearly in less pain.

Each treatment takes about a half-hour. The vet tech programs the machine for hip, elbow or back, and waves the wand over the targeted body part. Jana got lasered in both elbows, both hips, and much of her spine. The vet techs have treated wounds, post-surgical sutures, muscle sprains, and a variety of other ailments with the cold lasers.

The laser stimulates blood flow, which helps injured tissue to heal. The idea is that it will improve blood flow around the arthritic joints, reducing inflammation and therefore reducing pain. It seems to be working on Jana.

I am giving her small amounts of Rimadyl, as well as other anti-inflammatory supplements, but I am hoping to be able to reduce the pharmaceuticals further. She’ll now go to a maintenance schedule of treatments about once a month. I am sure that each dog reacts differently to treatments, but I have to say this one is worth trying if your senior dog is stiff or painful.

Food Before Thought

As Deni and Albee prepared to head off to a Rally Obedience class the other night, we discussed when to feed the dogs their dinner. Many trainers over the years have advised their human students not to feed dogs before training class. The dogs work better when they are hungry, is the claim. Deni and I pondered this, wondering whether it was good advice, anthropomorphism gone amok, or just plain silliness.

If it is an attempt to look at dogs through human eyes (the anthropomorphism gone amok theory), I guess it can be argued that really wanting something might make a being focus harder on what he or she has to do to get it. Therefore, if the dog really, really wants food, wouldn’t the dog focus harder on figuring out how to get it? Might sound plausible … except for a few problems. One is that the tiny tidbits of food a dog gets as rewards in training hardly take the place of a meal. And, this theory demands that you ignore stacks and stacks of research about learning or concentration and hunger.

Kids do not learn well when they are hungry. A really hungry child, and, probably, a really hungry dog, simply does not focus well. Research showing this has led public schools in low-income areas to offer not only free lunches, but breakfast as well, in attempts to boost concentration and improve kids’ learning.

Adults’ performance also suffers if we don’t eat a healthful breakfast. We know this, yet somehow think that our dogs will focus and learn if they are hungry? Doubtful.

Some trainers make a comparison with human athletes and point out that athletes are unlikely to eat a large meal just before a workout. Sure, but if training class is at 7 p.m., that is not a valid argument against feeding the dog at 5. Anyhow, a Rally class, an obedience class, even an agility class has a lot more in common with a grade-school classroom or a desk job than a triathalon. The dogs are not asked to perform athletic feats for hours, or even minutes on end. They are asked to pay attention to their handlers, to ignore distractions, to figure out what is needed, whether it is touching the contact at the end of the dog walk, sitting and staying for three minutes, or walking on a loose leash. The demands are primarily mental.

But there’s another, more important element. When trainers talk about training, it’s hard to avoid mention of the four quadrants of operant conditioning / behaviorism. The positive reinforcement quadrant is the one we are most familiar with — rewarding behavior we like. Ostensibly, the advice to train hungry dogs ties in with this: The dogs will get food rewards for their performance, and better performance will lead to more rewards. It’s all good, right?

Let’s look at it more honestly. Depriving a being of something it needs in order to get it to do what you want is called … torture. Withholding meals, then providing minute rewards for compliance falls into the “negative reinforcement” quadrant — removing a negative when the dog performs the requested behavior is supposed to increase the likelihood of the dog performing the behavior. Late dinner is about as negative as it gets for some dogs!

I know that comparing delaying a meal with common negative reinforcement techniques like ear pinch is an exaggeration. But comparing dog training class to an athletic workout isn’t? The dog will (eventually) get a meal, so feeding after training is not really abusive. But it is unfair. And it exploits the complete control we humans have over every aspect of our dogs’ lives.

The advice to delay meals might have been conceived by trainers who worked with dogs that are less food-obsessed than golden and Labrador retrievers. I still think it is wrong. A meal and tiny little training rewards are not the same thing. If your dog is unwilling to work for the training rewards you are offering, it is not because you have fed him; it is because the rewards you are offering are not, in that dog’s mind, motivators.

The cardinal rule of any kind of motivational training is that the trainee — the dog — determines what a motivator is and therefore what the reward should be.

If your training treats only motivate your dog when he is ravenous, skipping dinner is not the answer. Try using better treats. Try using a tennis ball, a tug toy — anything that your dog loves — as a reward. I might be willing to work for several hours to earn a paycheck that will arrive next week, but Cali, Jana, and Albee will always choose the freeze-dried liver over the cash — and they want it now, please. In fact, they will choose liver over and over again, at every opportunity, regardless of whether they’ve had dinner.