A recent Freakonomics podcast featured various politicians talking about one idea about elections that they wish would die, go away, never be mentioned again. I like that idea because I have a long list of absurd ideas about dogs and other nonhumans that I wish would go away and die a miserable, lonely death.

High up on that list is one that is getting a lot of attention these days, due to the unfortunate publication of a new book by novelist Tom Wolfe: the idea that only humans use language. Though I am one of the few people I know who disliked Bonfire of the Vanities, I had some professional respect for Wolfe as a writer until I heard his interview on NPR about his new book.

Wolfe essentially suggests that if evolution occurs, it only happens to nonhumans. That’s bad enough. But what really got my blood boiling were his comments on language. In the interview, Wolfe made the absurd claim that no evidence of anything resembling a language has ever been seen in a nonhuman. Wow. He really should have done some very basic research, like a cursory Google search, before deciding that. There’s a lot of research out there on animals and language.

Wolfe uses “speech” and “language” interchangeably, which is already a clear indication he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Many languages exist that are not based on speech, the most obvious being American (or any other) Sign Language. Thousands of nonverbal people understand and use language; some even write beautifully. Many actual scientists, even some who believe that only humans use language, have published extensive research on language and how it is separate from and does not require speech.

Wolfe also claimed that speech / language is necessary for any sort of memory or planning. Hmm, how does he explain insects, birds, mammals who store food for the winter (and remember where they put it); any critter who finds his way home once he leaves the den, ever, or who leads his pack back to the marvelous carcass or other food source he’s discovered? Even bees remember and guide others to food sources they’ve found. Memory. Memory, communication, teaching … And wouldn’t pack hunting, as wolves do, require planning? Building a nest or den requires both planning and memory. There’s a lot of research on these topics, too.But t

But really. Let’s focus on dogs for a moment. To establish that these nonhumans use language, remember, and plan, all you really need to do is spend a few days with a dog. Watch a dog come up with really clever plans for appropriating a coveted bone or toy from his sibling, or walk a dog who remembers where that lovely dead thing she rolled in last week was, or see how excited the dog gets when she recognizes the drive to the dog beach?

I could list, literally, thousands of examples from my own experience, reading, research, and students’ and friends’ stories. So could anyone who has ever paid much attention to dogs, elephants, chimps, whales, prairie dogs, birds, or any of the many other nonhumans who use language. Memory is essential to learning anything; and it is clear that millions of critters, but especially, and most near and dear to my heart, dogs, learn, remember, plan, use tools, problem-solve, and manipulate humans.

My favorite comment on the interview came from an NPR listener who wrote that “It was the equivalent of interviewing an expert on evolutionary biology who never reads novels to get his opinions about how novelists can write better stories.” Yup. Stick to what you know: make-believe. Another good response is this column about why it matters when a famous writer dismisses evolution.

My favorite comment on the interview came from an NPR listener who wrote that “It was the equivalent of interviewing an expert on evolutionary biology who never reads novels to get his opinions about how novelists can write better stories.” Yup. Stick to what you know: make-believe. Another good response is this column about why it matters when a famous writer dismisses evolution.

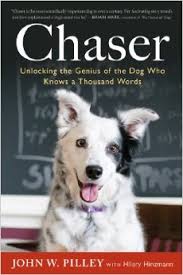

If you want to learn about language, read Chasing Doctor Doolittle or Beyond Words, both beautiful books about what language is and how various nonhumans use it. I’ve written several posts on this blog that address human communication with dogs and dogs’ ability to learn to understand human language. (I’ve never claimed that dogs have speech, and I do know the difference.) You can find those by searching this blog site.