An Immense World is neither a new book nor a dog book, but I enjoyed it so much that I wanted to share it!

An Immense World is neither a new book nor a dog book, but I enjoyed it so much that I wanted to share it!

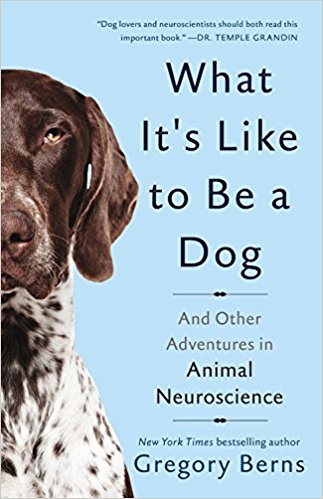

Ed Yong’s second book, subtitled “How animal senses reveal the hidden realms around us,” references philosopher Thomas Nagel’s essay, “What is it like to be a bat?” — then goes on to explore the Umwelt or “perceptual experience” of a being, whether human or not.

Spoiler alert: You won’t learn what it’s like to be a bat from this book. Or a dog, moth, dolphin, mole, or any other creature. You will explore the many-more-than 5 senses that various creatures use to perceive, navigate, and understand their worlds.

You won’t learn what it’s like to be a bat because you can’t!

Bats, and most other creatures have senses that are so astonishingly different from humans’ few, limited means of perceiving our environments that even with a deep scientific understanding of how those senses work, we still can’t imagine or experience the world as their owners do.

There is a lot of science in this book, as well as in the copious footnotes — worth reading; some are really funny! — the 44-page bibliography, and the endnotes. Whew. It did take me more than a month to read the book, though it’s only got 355 pages of actual content. I needed time to digest each sense (each chapter) before moving on to the next. And it’s not exactly light bedtime reading!

My favorite chapter may well be the one on echolocation (humans can acquire this skill!)… or maybe the one on color. Some insects and birds can see whole other dimensions of color that human eyes cannot perceive, literally millions of additional colors.

Yong explores the ways other creatures experience the senses we humans do have, then delves into senses we do not, such as the ability to use echoes and sound to see, or sense magnetic or electric fields and use them to map and navigate our environment.

A thread that runs through the book — and which has always driven my curiosity about dogs — is that our ability to even ask the questions that prompt us to study other animals’ abilities and behavior are limited by our own experience. Which is limited by our senses, perceptions — and willingness to consider that other creatures can do amazing things that we humans cannot.

Dogs’ phenomenal ability to detect and distinguish scents gets some attention, as does a discussion of how dogs perceive color. But no one creature is the star of this book. You’ll encounter familiar and bizarre animals and learn all sorts of interesting, if not terribly useful information: For example, the description of the inky-footprint test used to help determine that European robins know to migrate southwest in the fall using their ability to detect the Earth’s magnetic field is a great story … but a bit complicated for a cocktail-party chat.

If you’re a science nerd who loves animals, don’t miss this book.