When we are trying to understand why individuals — canine or human — behave in a certain way, we are trying to understand what motivates them. When trying to convince someone to do something he or she is not especially eager to do, we need to come up with a strong enough motivation to overcome that resistance.

For many dog trainers, food rewards are the only “motivator” they employ. Other trainers refuse to use food rewards in training, scornfully saying that dogs trained that way will work throughout their lives only for the food. In some cases, this might be true; skilled trainers, though, fade out the food rewards once a dog has learned a cue. Which leads to the interesting question of motivation: If the dogs are not working only for the food, what are they working for?

What do you work for? The satisfaction of a job well done? Money? The chance for a guilt-free rest or vacation? The admiration of your boss, colleagues, or friends? To impress your family? The pleasure you get from your work?

People work for many things. Some are tangible (money or food); some are external (popularity, praise, satisfaction) and some are internal (feeling proud of accomplishment, understanding the importance of the goal). The same is true of dogs (except maybe the money part).

What motivates you is as individual as you are. It is as variable as the situation or task at hand, your mood or energy level, where you are (in life or at a given moment), who’s nearby … any number of things can affect your motivation. What remains true is this: You decide what motivates you at any given moment or to perform any particular task. If you don’t care about money, no amount will drive you to do a task you loathe. If you are not hungry, the promise of a snack is unlikely to propel you to quickly complete your homework.

Next time you are having a hard time getting your dog to do something that you want her to do, think about motivation. Try a different motivator. Maybe you are asking her to do something that is very important to you but irrelevant or even unpleasant to her. Examples range from calling your dog to you when she is playing at the dog park or chasing a squirrel to asking her to pick up an object that is heavy, awkward, or just plain inconvenient to hold. In many cases, she’ll be willing to do as you ask — given the right motivation.

I know that it’s hard to be more interesting and appealing than a fleeing squirrel. But waiting a moment, until the squirrel reaches a nearby tree, perhaps, then calling the dog and offering a really tasty treat … well, now you might be getting somewhere. If your dog loves to play tug, use a few rounds as a reward when she does something that is really important to you — like picking up her heavy, awkward food bowl after dinner. Improve your tennis-ball-obsessed pup’s recall by rewarding her for a quick response with a few throws.

Finding the right motivation sometimes requires creative thinking on your part. It also requires looking at your dog as an individual. To figure out what motivates your dog, pay attention to what your dog pays attention to. What turns that light on in her eyes or gets her running over to you? Dogs whose owners say they are “not interested” in food might discover a culinary bent in their pooch when they offer freeze-dried liver or bison jerky or bits of roast beef. Maybe you haven’t hit on the right toy to turn on your dog’s inner retriever or you haven’t found the scratch spot that’ll have him not only picking up but washing and drying the dishes — just to get a little more of what you are offering.

We all will work for something. We will often do even unpleasant chores for the right reward. The trick, in every relationship, is figuring out which rewards work. You’ll know when you find the ones that work — but remember, make sure that the dog knows that it’s always her decision.

Author: Pam Hogle

Rethinking Obedience

“The walls and grids that restrain your animals restrain also your own knowledge.”

“The walls and grids that restrain your animals restrain also your own knowledge.”

— Vicki Hearne

What I call “old-school” dog trainers — those who operate from the assumption that the human has “to be the alpha” in his or her relationship with a dog — don’t, in my opinion, credit dogs with much in the way of cognitive ability.

Some, like the 1920-era European trainer Konrad Most, bluntly state an approach to education that many of us would recoil from today: “In the absence of compulsion, neither human education nor canine training is possible.” Others, like William Koehler (circa 1960s), give rational-sounding advice: “Lay down a set of rules, and see that your dog lives by them.” But the means used to accomplish that goal are harsh and authoritarian.

What these trainers share is an emphasis on punishment over motivation or reward and an expectation that a dog should offer instant, precise obedience to any command given by a human. The expected response is almost robotic in its uniformity and immediacy.

Trainers with these expectations do not believe that dogs can — or should — think or be part of a decision-making process. No, the dog should know who’s boss and, according to Most, “do what we find convenient or useful and refrain from doing what is inconvenient or harmful to us.”

While both Most and Koehler were both enormously influential in the development of dog training, much about their approach is antithetical to the goal of raising a thinking dog.

Demanding instant, precise obedience to all commands in all situations does not allow for the dog to think or process the command in any way. When you expect instant, unquestioning obedience from your dog, you are essentially prohibiting him from thinking. In human relationships, we talk about such expectations this way: “When I say jump; you may ask only, ‘how high?’ ”

To raise a thinking dog, that is, to use a cognitive approach to your dog’s education, you must have expectations that not only allow for but encourage the dog to think and solve problems. The cognitive dog needs to learn, understand, and, ultimately, buy into a shared goal. Expecting unquestioning obedience at every request, mapping out not only the end result but every step the dog must perform to get there does not — cannot — allow dogs to think conceptually about what you are trying to accomplish, learn to solve problems, or offer a different (maybe better!) solution.

Granted, there are situations where an instant response is necessary — if your dog is unthinkingly following a bouncing tennis ball into a street, for example. But developing your dog’s cognitive abilities does not prevent you from also teaching your dog a strong recall and an “emergency recall” cue that, when taught and practiced with the highest-value treats possible, will ensure an automatic response in a true emergency.

There are many ways to lead or manage (or parent). Those of us who want to share our lives with thinking dogs should be wary of dog professionals who talk a lot about alpha roles and hierarchical relationships. Instead, we should look for ways to develop our dogs’ considerable cognitive abilities. Start by figuring out what motivates your dog. Read future blogs for tips on how to do that and more.

Are dryer sheets dangerous to dogs?

Cali loves to grab the dryer sheets that often fall to the floor when I am folding clean laundry. It never occurred to me that her habit of grabbing and shredding them could be a problem … until I read this blog post: Four Household Dangers. Keep your puppies safe!

Teaching or Training?

Puppies, like babies, are born with the potential to learn and problem solve and think. They are innately curious and begin investigating their world even before they open their eyes.

Our job is to develop these skills in our puppies and dogs by providing opportunities for them to learn and develop their conceptual thinking abilities. We can expose them to lots of novel items and situations and provide encouragement and motivation. We can also be on the lookout — especially with puppies — for opportunities to turn potential problem behaviors into desirable, adorable, and even helpful skills!

Dogs who are taught, especially by handlers who use methods that encourage problem-solving, become better problem-solvers. A study called “Does training make you smarter?” compared dogs who had received training with dogs who had not. Dogs who had received training solved a problem — opening a box that had a pad that could be pressed by the dog’s paw — spent more time trying to open the box (and were less likely to seek help from their owners) than dogs who had no formal education. The study’s authors speculate that trained dogs have “learned to learn” in a way that unschooled dogs have not.

But, and this is a big but — not all education is equal. There are many approaches to teaching or training, and the methods you choose will affect more than just how fast your dog learns — it can affect the bond between you and your dog, and it can shape or reflect your attitudes toward dogs. And it’s not just the method. The words matter, too.

I make a distinction between training dogs and teaching them because I think the word choice reflects a difference in attitude and goals.

Training dogs is what I call educational approaches that are narrowly focused on eliciting specific reactions to cues or commands. The trainer has a clear end result in mind for each command. The trainer says, “sit;” the dog sits. Practice emphasizes precision of the dog’s response, speed of the response, and the dog’s ability to respond quickly and precisely even when distractions are present.

When I refer to teaching, on the other hand, I am referring to a process that develops the dog’s thinking and problem-solving abilities. The teacher’s goal is to give his or her students the tools and the confidence to figure out what to do in a variety of situations. Sometimes, a teacher might seek a precise response, like the sit; other times, the teacher makes a request that requires the dog to figure out what to do. “Find a pen” gives the dog a goal but no precise instructions for reaching that goal.

Teaching brings the dog to a level of independent thought and problem solving that enables him to respond to a command or cue that is as vaguely defined as “find a pen;” training does not.

Any approach to training or teaching is based on an underlying mindset or set of assumptions: assumptions about what dogs are capable of learning; assumptions about how dogs learn and how much of what we say and do they actually understand; and assumptions about what the dog-person relationship should be.

Trainers who do not believe that dogs are capable or reasoning or problem-solving are unlikely to put any effort into developing these skills in the dogs they train. Trainers or handlers who believe the dog’s “job” is to be obedient and submissive are unlikely to tolerate a free-thinking dog. Some trainers talk about “getting dominance” or “being the alpha” as ways to ensure that dogs remain obedient and submissive.

Methods of dog “training” or education can be placed on a continuum that ranges from those that do not encourage the dog to think at all to those that practically make the dog do all of the thinking. The Thinking Dog blog will teach you to recognize various approaches and their goals — and encourage and equip you to explore methods that help your dog become the best thinking dog he or she can be.

The Great Outdoors

We’re about to embark on our first camping adventure. It will be camping-lite, with lots of people and dogs heading to a group campsite at a family “camping resort.” Nothing too ambitious for us city girls.

I’ve been fortunate to be able to borrow needed equipment from friends who will also be on this adventure. But what about Jana and Cali?

What great luck, then, that I got an email from doggyloot (visit at your own peril; the site can be dangerous) titled “Make your pooch one happy camper!”

With great relief, I opened the email to see what gear my girls would need for their weekend in the woods.

How about a dog bed that converts to a sleeping bag? Add to that a comfy dog-size tent. The tent has windows on three sides (with nylon covers to block the light) and a zip-close door, also with mesh screen and solid flaps. Does each dog need her own, I wondered. Can they share? Why can’t we all bunk together? A less-fancy option is a shade shelter, which is essentially a tent with one fully open side — no door, mesh or otherwise.

How about a dog bed that converts to a sleeping bag? Add to that a comfy dog-size tent. The tent has windows on three sides (with nylon covers to block the light) and a zip-close door, also with mesh screen and solid flaps. Does each dog need her own, I wondered. Can they share? Why can’t we all bunk together? A less-fancy option is a shade shelter, which is essentially a tent with one fully open side — no door, mesh or otherwise.

For hiking, an insect-repellent bandanna is recommended, a travel first-aid kit, and perhaps a doggy backpack to carry the gear. And, since tenderfoot pooches work up an appetite on the trail, some Turbopup doggy meal-replacement bars, available in bacon or peanut butter flavor. Yum. Add some doggy wipes for on-the-trail grooming needs and an insect-repellent blanket for use in camp, and they will be all set …

And I was just planning to pack some beef-bison jerky (they are addicted), a couple of chew toys, and their swim suits. Silly me. Maybe I should revisit my original idea — a doggy camper, like these, featured on HuffPost not long ago. After all, my princesses are not used to roughing it.

What Is Cognitive Education for Dogs?

Welcome to an all-new, improved Thinking Dog blog! It is re-launching with a new focus — cognitive approaches to educating dogs.

What does that mean? Think of it as a contrast to the more traditional approaches, many of which use force, to train dogs.

Cognitive-based dog education means teaching dogs to think their way to becoming their best selves.

Their best what, you ask? Well, that answer is different for every dog — just as it is for every person.

It’s not a new idea: In 1963, Clarence Pfaffenberger wrote a book called The New Knowledge of Dog Behavior. A line in that book beautifully captures the essence of cognitive education. Pfaffenberger writes that the first time a puppy to removed from his or her littermates for training, the puppy is given “the dignity of being an individual.” All dogs deserve this. It is this understanding that forms the basis of cognitive education for dogs.

In 1995, Vicki Hearne published a classic piece, “A Taxonomy of Knowing: Animals Captive, Free-Ranging, and at Liberty.” In it, she describes the ideal relationship between a human and a non-human partner (most of her examples are dogs): the team shares a goal, recognizing and respecting the unique abilities that each member of the team brings to the joint pursuit of that goal.

An animal working at liberty, Hearne writes, is one “whose condition frees her to make the fullest use of some or all of her powers.” A great example is a search-and-rescue team. The dog brings amazing powers of scent detection and tracking to the partnership; the human brings logistical planning abilities and much more. The point is, neither partner, alone, could be as successful in the goal of finding a lost child as they are as a team.

Dogs in at-liberty partnerships are being the best that they can be. Cognitive education can get you and your dog there.

Remember Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Psych 101)? Basic stuff like food and shelter are at the bottom. More esoteric needs, like social acceptance and aesthetic enjoyment, are higher up. The highest level is self-actualization — being the best you that you can be. That is what cognitive educators want for each and every dog.

As Pfaffenberger acknowledged, each dog is a unique individual with likes, dislikes, strengths, weaknesses — and an idea of what he or she wants (and does not want) to do. Cognitive educators understand this and teach each dog as an individual. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to training.

This approach enables each dog to be the best (fill in the blank) that he or she can. Some dogs can become fantastic service dogs; others are destined to work as scent detection or search and rescue dogs, serve in the military, or provide loving companionship to their humans. Some pets are great athletes who enjoy dock diving; others prefer Rally, flyball, agility, or freestyle dancing. Whatever your pet’s skills and preferences, you, as a cognitive educator, friend, and companion to that dog, can help your dog explore and develop and grow.

If this sounds like something you believe in or want to learn more about, stick with The Thinking Dog blog. We’ll be exploring cognitive education from every angle — who does it and how; what it looks like in daily life; how to think like a cognitive educator; what dogs are telling you about their likes and dislikes and how to better understand them … and so much more.

Check back often, subscribe to the blog, and be sure to share it with all of your dog-loving friends.

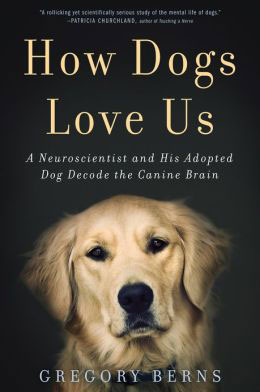

How Dogs Love Us

Gregory Berns got the crazy idea of training his dog to lie still in an MRI machine, in the hope it would provide some insight into dogs’ thinking. What he found brings scientific proof to something every dog person knows — that dogs read us, anticipate our behavior, and act on that knowledge. Dogs, in short, have theory of mind. Berns rightly argues that this scientific evidence must change the way we think of and treat dogs.

Gregory Berns got the crazy idea of training his dog to lie still in an MRI machine, in the hope it would provide some insight into dogs’ thinking. What he found brings scientific proof to something every dog person knows — that dogs read us, anticipate our behavior, and act on that knowledge. Dogs, in short, have theory of mind. Berns rightly argues that this scientific evidence must change the way we think of and treat dogs.

What’s especially wonderful about this story is that, at least at the beginning, Berns is not an especially savvy dog person. He loves his dogs, treats them extremely well, but hasn’t spent a lot of time trying to communicate effectively with them or train them. By the end of the book — or maybe by a few months into the research — he’s become convinced that dogs communicate and function on a very high level and that “the key to improving dog-human relationships is through social cognition, not behaviorism.” Quite a journey … in fact, it’s the same journey that I hope to push my students along in Bergin U classes on dog training, canine-human communication and understanding the dog’s perspective. (Any current Bergin U students reading this might as well order their copies now … this book is destined to become required reading in all my classes.)

The book is filled with fairly complex scientific concepts, but it is written beautifully and clearly. It is very easy to understand and, like a good adventure novel, pulls readers along with foreshadowing and suspense. I especially love the long discussion of the ethical issues Berns and his team faced in setting up the research and the insistence of all the human researchers that the dogs would always be free to opt out, at any time. I also love the dog-centric approach the research takes (read the book to find out what I mean!). This book — this whole research study —is a testament to the amazing possibilities that exist when humans acknowledge their dogs’ abilities, treat them as partners (rather than as property or as slaves), and engage with them in a respectful, positive manner.

Because I am nut for precise language, I do have to quibble with the title. Berns does not actually show HOW dogs love us. He does show, I believe, that they DO love their human family members. While he can’t really show us what dogs are thinking, though, he has shown a way to understand their likes and dislikes — and perhaps opened the door to a better ability to read in dogs other emotions that humans and dogs share.

What are the BEST dog toys?

A friend recently asked me for advice on addressing some behavior issues with a young golden retriever. Since I have extensive experience with young golden retrievers, I quickly deduced that the main issue was that the golden’s energy level far surpassed that of her human. She needed a way to burn off some of that energy, something that would provide mental stimulation as well. Bored, smart dogs with energy to burn can be a dangerous combination!

I suggested several chew toys and treat toys, both of which will engage the attention of food-motivated dogs (goldens define food-motivated) and pose a mental challenge. In other words, burn off physical and mental energy, keep the dog busy, and make everyone’s life a little more peaceful. Sounds great, right?

These toys work for any dog who is willing to put some effort into obtaining a yummy reward. All have been thoroughly vetted by an expert panel consisting of:

- Jana, a 10-year-old golden who will work for hours for the tiniest morsel of food

- Cali, an 11-month-old golden who has about a 20-second attention span, but who enjoys most of these toys and will actually play with some of them for as long as half an hour (!!)

- Albee, a 2-year-old Labrador who prefers not to have to work for her food after spending a long day at the office, but who also enthusiastically approved several of these toys

Chew Toys

Our newest favorites are all in the “Busy Buddy” family — The Bristle Bone, which is used with rawhide or cornstarch rings, is beloved by all three expert testers. Albee has managed to de-bristle the bristle rings, though, which makes it really easy to get the rawhide and also diminishes the teeth cleaning action of the toy. The Jack toy is Cali’s favorite, but Jana has managed to take it apart several times, making it far too easy to slip off the rawhide ring and devour it. The Ultra Stratos is a new addition to this toy collection and seemed promising, but again, Jana managed to defeat it fairly quickly. Now that we have several of these Busy Buddy toys, I make up new configurations of rings, bristles and rawhide, and I am going to get smaller rings to make it even harder for top expert Jana to get to the rings. Still, she will spend a good hour chewing on one of these toys if I manage to screw it together tightly enough. In my book, that is a huge success.

I can’t write about chew toys without mentioning old standbys: Rawhide, bones, Nylabones, and antlers.

All members of the expert panel love antlers, but I stopped getting them because we got a soft one once; Jana managed to eat a couple inches of it before I noticed, and she got really sick. In general, though, they are safe, long-lasting chews. If you get them, purchase from a U.S.-company that uses wild-shed antlers. Antlers don’t splinter like bones, and they are all natural.

Bones can be OK if they are fresh, boiled just a couple min to kill germs. When they’ve been around a while, they get brittle, though, and they can splinter or crack. That is how Jana cracked a molar recently, a very expensive lesson! We sometimes get the ones with some gristle still on, give them to the dogs outside (separated so they don’t kill each other) and throw them out when the bone part starts to look dry.

Cali has recently discovered Nylabones, and she’s a big fan. Jana and Albee will occasionally get into a chewing frenzy as well. These last a long time and are safe chew toys.

I generally avoid rawhide, since dogs can bite off large enough chunks that they can choke, and since most rawhide is treated with really toxic chemicals. There are some U.S. made brands that claim to be organic, but I still stay away from rawhide. There are so many preferable toys to choose from.

Treat Toys

These are great for mental stimulation as well as fun. You can feed the dog part of each meal in one or more of these, which will burn some mental energy.

Our experts give 4 paws up to:

Our experts give 4 paws up to:

- The classic Kong, stuffed with … just about anything. Some favorites are kibble mixed w/peanut butter or yogurt and frozen; kibble softened in chicken broth (or warm water) and frozen; plain yogurt (also frozen) — this one is messy and best enjoyed outside. There are literally hundreds of Kong “recipes” if you Google “Kong stuffing.”

- Squirrel Dude is still the reigning champion at our house. Jana loves him and cannot get all the food out. (The other dogs are less willing to work that hard, but he’s very popular will all testers.)

- Busy Buddy Twist n’ Treat — good with peanut butter and kibble. Plain kibble falls out too easily.

- Kong Genius toys are challenging — Cali hasn’t mastered them yet! Jana loves them. Albee doesn’t want to work that hard. They link together to make it even harder to get the food out.

- Other favorites, beloved by Albee in particular, are the Omega Paw Tricky Treat Ball and the TreatStik. These both hold kibble and the dog bats the toy around to make the kibble fall out.

- And of course, Jana’s longtime favorite, the Orbee ball with a large biscuit stuffed inside. She has to break the biscuit into small enough pieces that they will fall out of the small hole. She’s gotten so good at this, though, that unless the biscuit is very hard to break, she’s done in a few minutes.

General advice — Avoid toys that use a specially designed treat. The refill treats are usually overpriced. There are many, many toys that can be filled with the dog’s kibble, which means you can make the dog work for part of each meal. The only exception I’ve made is the Busy Buddy toys, because they are among the few toys that keep Jana busy for hours (really!) and the rings last a while. I also advise avoiding the ones that are a harder plastic (like the Buster Cube); they are very noisy on the floor as the dog bangs them around to get the food out.

This stuff is all available on Dog.com and Amazon. Local St. Petersburgers can get them at Pet Food Warehouse, a wonderful, locally owned pet store. If you get on their email list, you get a monthly newsletter with a $5 coupon!

Sick Puppy? Keep Her Hydrated

Our little Cali has been ill with stomach “issues” for about 2 weeks now. Along with getting lots of great care from her vet, who is trying to figure out what’s wrong, I’ve been working hard to make sure she doesn’t get dehydrated. It’s hot and humid here in Florida, and despite being sick, Cali still wants to run and play.

She’s drinking (homemade) chicken broth and eating bits of chicken, but I needed to replace the fluid and minerals she was losing due to her, uh, issues at both ends.

Our vet, Dr. Landers, recommended getting Pedialyte and making it into ice cubes. I thought about coconut water and did a little research. I knew that coconut water was touted as a natural way to rehydrate and replace lost electrolytes for active humans. I discovered that it has the same benefits for dogs — and is a lot less expensive than Pedialyte. It also comes in natural, unflavored form with no added sugar.

So, I got some and bought a set of ice cube trays and … lo and behold, all of the dogs love popsicles! Cali did not like drinking the Pedialyte, but she gobbles down the ice cubes. She also loves the coconut ice cubes. Albee, who, like Cali, loves to munch on ice, came over to see what the fuss was about. She turned up her pretty little nose at a plain ice cube when she realized that Cali was getting something different. Even Jana, who hasn’t wanted to munch an ice cube since she was about Albee’s age, got into it. She loves the popsicles too.

According to the Bunk Blog, coconut water is used in many tropical places to rehydrate people with gastrointestinal issues, and it “is very low in sodium and chlorides, but rich in sugars and amino acids.”

We might just make coconut popsicles a regular part of our dogs’ summer diet!

Talking Dogs

I got some sad news today. A beloved professor (then colleague and boss) passed away suddenly yesterday.

My favorite memory of Bob is from the day I presented the research I had done for my final master’s project. I (of course) wrote chapters for a still-unpublished book about dog-human partnerships. The chapter I was presenting was on dog-human communication. Throughout my presentation, I referred to the dogs, Wylie and Jana, as “saying” things. At the end of my presentation, in his typical dry style, Bob said “What I find most interesting about your research is how well your dogs talk!” We all had a good laugh.

My dogs might not be talking in the way most humans do, but all day, they’ve been saying, “Why are you so sad?” and “How can we make you feel better?” Even though our dogs don’t speak to us in our preferred human language, they sure do talk to us … and understand our feelings.

I’ll sure miss Bob. My “talking dogs” will, too.